Chapter 3: Preparation for a new resistance: C.P.M.

“Strike one to educate one hundred”

Chapter 3: Preparation for a new resistance: C.P.M.

In the winter-spring of 1969-70 the CPM grew to be one of the key

organizations in Milan. It continued to operate inside the factories where

the C.U.B.s and study groups that had given birth to the collective were

based. CPM consciously linked wage and working conditions struggles to the

larger struggle against world imperialism. Slogans like “Indochina- Italy:

the same struggle” and “Imperialism-reformism: the same chain”, were typical

of their mass political line.

An important new element in the Milan situation was a movement of

vocational students, representing the spread of student rebellion into the

working class. There were 80,000 such vocational students in Milan, the

most of any city in Italy. These young workers labored during the day and

attended school at night to complete their technical training or apprenticeships.

Their student/worker movement rebelled against the long hours, arbitrary

and vindictive school discipline, and the high tuition fees. Led by CPM militants

at the Feltrineli Technical Institute, thousands of vocational students

had a large demonstration demanding an end to tuition fees. The slogans

included: “The union=workers police”, “Administrators + teachers–servants

of the bosses”, and “The bourgeois state cannot be changed, it must be destroyed!”

CPM was a large political influence in the student/worker movement in Milan.

The collective was still only an intermediate stage of development.

It was not in its own eyes the revolutionary vanguard, but only like- minded

militants who had come together to consciously search out the path of transition

from spontaneous mass movement to revolutionary organization. As an IBM study

group paper put it: “Struggles on the factory floor must be integrated into

the world-wide class struggle, particularly in its European expression.”

The CPM found itself in disagreement with the extra-parliamentary

Left groups over their assessment of the national labor-management contract

fights of the “Hot Autumn” of 1969. These battles involving 5 million unionized

workers began in September 1969. Most of the New Left had been overly optimistic

about their potential results, viewing the wage struggles in themselves as

“revolutionary” and the bourgeoisie about to “surrender unconditionally”.

But in December after the national wage contracts had been signed the reformist

unions had come out of the fight numerically and organizationally stronger,

and spontaneous mass struggle in the factories had not only ebbed temporarily

but had been co-opted. Unprepared for this set-back to the rank-and-file

C.U.B. movement the mood of the New Left now swung from wild optimism to

deep pessimism. CPM disagreed with the shallowness of the New Left’s understanding.

CPM having reached a more political assessment of tbe short-comings of the

C.U.B. movement now also saw its strengths more realistically than the rest

of the New Left.

At IBM-Italy the revolutionary study group had taken a leading role

in the “Hot Autumn” struggles. A manager had been fired at the IBM Vimercate

factory “for having been part of a group politically opposed to management”,

and for thus having supported the workers’ demands. When the unions defended

the company, a spontaneous struggle broke out. The study group reported:

“The workers of IBM stop working and meet in mass assembly… the

decision of the Internal Commission is totally repudiated and the union body

itself is pushed aside and denied any authority to lead the workers: the

Internal Commission is forced to demand that management reverse its decision.

It is decided by the workers to constitute themselves as a permanent mass

assembly linking together the fight against repression with the contract

struggle. It is a memorable day for IBM, and for the autonomy and the class

momentum that the workers express in totally spontaneous forms; it is lived

through in an atmosphere of high tension. The spontaneous strike lasts the

whole day changing from a mass assembly into a parade which snakes through

the entire factory and then reconvenes in mass assembly to decide the forms

of struggle for the following days.”

IBM management was forced to back down. The IBM study group concluded:

“The balance sheet is undoubtedly positive: the spontaneous strike

and the achievement of the mass assembly… constitute the new political

base from which to move forward.”

But “… political insufficiency and a certain dose of opportunism

present in the group permits the unions to quickly reabsorb the movement

within the channels of their contractual logic.

“The political vacuum in which factory struggle takes place is a

sign of the progressive lessening of tension. From time to time some incident

just happens, some big shock, such as clashes with die-hard scabs, or incidents

involving destruction of their cars, to which no one knows how to give proper

political weight and a proper outcome…”

Between November and December 1969 the group analyzed its own crisis

which was expressed by the contradiction between “the success of the general

goal of mobilization of the working class and the failure of the presupposition

of autonomy which was to be its foundation.”

According to this self-criticism: “To turn to all the workers …

has been to pretend not to notice reality, to not act to identify the Left

in the factory and within it find a political space to constitute oneself

as a point of reference…. At IBM we wanted to be the point of reference

for all the workers and we weren’t a point of reference for anyone. We won

everyone’s sympathy and we were considered a dissident fringe of the unions;

we wanted to change the direction and the terrain of the struggle at IBM

in opposition to the union’s choices and we were almost always the unconscious

instrument of the unions. Errors were committed in mistaking for real political

consciousness a generic opportunism of the silent majority type which monotonously

sides with the winning proposition.”

The study group concluded that there was a need to go beyond the

spontaneous level of struggle in the factory, and to raise the level to

that of the anti-revisionist and anti-imperialist struggle. To start this

an exemplary action was carried out. During ceremonies IBM held to inaugurate

a new computer model top directors of the Italian IBM affiliate as well

as u.s. IBM management were present at the plant in Milan. CPM, which the

IBM study group had just joined, put up banners inside the IBM plant with

slogans like “IBM Produces War”, “IBM in Italy, Imperialism at Home”, “On

Strike, Out With The Servants of Imperialism”. As a result the u.s. IBM

directors were forced to enter the building by a service entrance.

The IBM study group’s radical self-criticism was part of their political

interaction inside the Metropolitan Political Collectiye (CPM) with the Sit-Siemens

and Pirelli groups, who were undergoing a similar crisis over spontaneism.

The decision by the IBM study group to join CPM at this point came out of

their understanding that to make this qualitative political leap to anti-imperialism

and anti-revisionism, the factory movement needed to go beyond the political

and organizational limitations of the C.U.B. and factory study group forms

of struggle. The IBM study group described the problem as follows:

“The crisis of the Pirelli C.U.B. (which resuited from the collapse

of the struggle after the contract was signed, and the failure to organize

a working class vanguard within the factory), the impasse faced by the IBM,

Sit-Siemens and other factory groups which have sprouted like mushrooms

during the hot autumn contract fight’s some of which are just as rapidly

falling apart, demands a fundamental change of the political assumptions

underlying their actions and a radical rethinking to justify their existence

outside of the trade union organizations and the left [electoral] parties.”

The IBM study group concluded that the “Hot Autumn” factory uprisings

had decreed the death of “groupism”. From now on the factory struggle had

to be seen in the framework of a wider class struggle on the European and

world level. As far as the terrain of the struggle was concerned the study

group concluded “above all, the class struggle in the metropolis is defined

in revolutionary terms whose outcome is represented by PEOPLE’S ARMED STRUGGLE”.

In December 1969 a small group of Catholic laypersons held a conference

at a religious institute in Chiavari, a small port city on the Ligurian coast

not far from Genoa. The “Catholic laymen” were disguised CPM representatives.

The secret meeting discussed a proposal, put forward by Curcio, Cagol and

others, that CPM prepare for immediate armed struggle. A military-political

organizational plan was outlined. The debate that ensued caused sharp divisions

in the CPM between those who wished to advance the struggle at that point

primarily by violent mass “social confrontation” in strikes and demonstrations,

and those who wanted to begin a systematic plan of urban guerrilla warfare.

There were also differences on timing, with some holding that a longer period

of political-organizational preparation was necessary before forming guerrilla

forces. This debate was to continue throughout 1970 until a second secret

meeting in October of 1970, when the two groupings split and the Red Brigades

were formally launched.

One interesting result of the Chiavari conference was a long theoretical

document, entitled Social Struggle & Organization in the Metropolis,

which systematized the political line of the collective. In it, the CPM comrades

drew up “a balance sheet of concrete political experience and outlined plans

for future political work”. In this document a definition of proletarian

autonomy is given:

“We see in proletarian autonomy the unifying content of the struggles

of the students, workers and technicians which prepared the way for the qualitative

leap of 1968-69.

“Autonomy is not a fantasy or an empty formula for those who, in

the face of the system’s counter-offensive, nostagically cling to past struggles.

Autonomy is the movement for proletarian liberation from the comprehensive

hegemony of the bourgeoisie and it coincides with the revolutionary process.

In this sense autonomy is certainly not a new thing, a last-minute invention,

but a political category of revolutionary Marxism, in whose light the consistency

and direction of a mass movement can be evaluated.

“Autonomy from: bourgeois political institutions (the state, parties,

unions, judicial institutions, etc.), economic institutions (the entire capitalist

productive-distributive apparatus), cultural institutions (the dominant

ideology in all its manifestations), normative institutions (habits, bourgeois

‘morals’).

“Autonomy for: the destruction of the whole system of exploitation

and the construction of an alternative social organization.”

“It is necessary today to redefine the very concept of revolution

in the light of objective conditions and the real development of the autonomous

movement of the european proletariat….

“Revolutionary process and not revolutionary moment.

“The Brazilian revolutionary Marcelo De Andrade writes: ‘Before the

unification of world capitalism by yankee imperialism, the proletariat was

able to arm itself by unarmed means, that is they could first organize themselves

politically and develop the political struggle and unarmed violence up to

a certain point, to then profit from the social, political and military disasters

of the ruling classes of their respective countries to arm themselves and

seize power…. Today, given that the possibility of an inter-imperialist

war is historically excluded, an alterative proletarian power must be, from

the beginning, political-military, given that the armed struggle is the main

form of the class struggle.’

“Implicit in incorrect conceptions current today in Italy regarding

the relationship between mass movement and revolutionary organization is

the image of a process of this type: first we develop the purely political

struggle, winning the masses to the idea of revolution, only then when the

masses have become revolutionary we will make the armed revolution….

Intermediate objective: the construction of the Marxist- Leninist party.

“Reality itself pulls us away from suggestions of a false alternative.

The social dimension of the struggle and the highest point of its development:

the struggle against generalized repression, already constitutes a revolutionary

movement…. When it is possible to get 4 years in jail for not having attacked

a cop, a choice is imposed: either one hides in the marsh of renunciatory

reformism, or one accepts the revolutionary terrain of the

struggle…. The bourgeoisie has already chosen illegality. The long

revolutionary march in the metropolis is the only adequate response.”

“SINISTRA PROLETARIA” —

THE SHIFT FROM LEGALITY TO ILLEGALITY

In July 1970 the CPM collective began publication of a theoretical

magazine called Sinistra Proletaria (Proletarian Left). CPM had previously

published agitational leaflets using this title but the appearance of the

magazine reflected a new stage in the ongoing struggle over the question of

armed struggle inside the collective. With the appearance of Sinistra Proletaria

the collective dropped the name CPM and took on that of Proletarian Left.

This marked the beginning of the Red Brigades in embryonic form.

SP/CPM pointed out that the struggle within the movement for a higher

level of organization was the critical step:

“To organize ourselves is not easy, it’s a struggle… it is a struggle,

first of all against spontaneism and confusion, against the tendency to accept

the frontal assault which the bosses would like to impose on us, we need

an all-inclusive organization which is able to carry out the struggle we’re

engaged in, not in one factory or in one neighborhood, but in the whole

society…. The proletariat has gone through the first stage of struggle:

that of spontaneous clashes everywhere and anywhere, where it’s go for broke,

risking everything, and it now begins to understand that the class struggle

is like a war. One has to learn how to strike without warning, concentrating

one’s forces for the attack, dispersing rapidly when the enemy counterattacks….

When the american army invaded Cambodia, it did not find even the shadow

of a Vietcong, later it had to endure sudden attacks everywhere in South

Vietnam, in the rear areas where it was weakest. This is the model to follow….”

“…. whoever thinks they can attack us with impunity, fire

us, beat us up, must meet with a hard answer. But not only that: we

must learn to strike the enemy first, when it is still unprepared…. We

must build workers cells for defense and attack, we must learn to protect

our backs, to defend a comrade when they are assaulted…. The organization

of violence is a necessity of the class struggle.”

In addition to doing theoretical battle against the backwardness

of the movement, SP/CPM sought to deepen its roots in the factories and

generalize the anti-capitalist struggle to Italian society as a whole. And

they put special emphasis in the summer of 1970 on building a clandestine

base in the key

factories of Sit-Siemens, Alfa-Romeo, FIAT and Pirelli.

During this same period SP/CPM joined with Continuous Struggle and

other groups to challenge the reformist PCI’s attempts to co-opt the mass

discontent with a legalistic program tied to a return of a Center-Left

government. They ambitiously initiated an aggressive campaign called “Let’s

take the city” which called on workers “to take, not ask for” housing, transport,

books, food, etc.

Between the summer of 1970 and February 1971 (when it ceased to exist

as a public organization) SP/CPM led a series of mass occupations of abandoned

housing in the Red working class neighborhoods like Quarto Oggiaro, Gallaratese,

and MacMahon which ring Milan’s outskirts. The popular mass slogan “housing

should be taken, don’t pay rent” was put out in June 1970.

In these housing struggles SP/CPM emphasized the need for the masses

to prepare themselves to militarily meet the violence of the State, pointing

out that these struggles were part of a wider struggle for State power. The

level of mass support for these housing occupations was very high, and women

played a leading role in the many violent clashes with the police. The poor

families in each building had to fortify it and organize themselves to fight

off police attacks to evict them. Despite the PCI’s denunciation of these

occupation movements as adventurist provocations which would only help the

Right, a number of them were successful, such as one in September 1970 in

the Gallaratese neighborhood which won badly needed housing for 20 proletarian

families.

This struggle took place under the leadership of a committee set

up by Sinistra Proletaria (SP). The target was a 14 story empty apartment

building, belonging to public housing authorities, in the Red proletarian

Gallaratese neighborhood.

“The committee nominated three household heads to take care of technical

problems. Only the members of this small committee were to know the day of

the occupation…. The overall problem consisted in carrying out the occupation

by surprise…. The occupation of the apartment was decided for the night

of September 24-25. Only the committee of three knew the exact day…. The

families left in separate waves: this way if the police followed and stopped

one automobile the others could still continue….

“A comrade acting as courier was supposed to be stationed near the

apartment building to relay a warning if the police were nearby…. The police

were not there…. By 10:45 p.m. all the families were in the building….

The action had been very swift and silent…. A rudimentary defense was immediately

organized with… bricks and stones brought inside…. The police only

found out about the occupation the next day by reading the newspapers!

During the night the walls of all the nearby houses were plastered with a

special edition of the Sinistra Proletaria newspaper entitled WHO DO OU HOUSES

BELONG TO? and leaflets entitled Housing should be taken, don’t pay rent.

An enormous banner saying OCCUPIED HOUSES fes- tooned with red banners made

the police furious….

During the morning the biggest mistake of the action was made. Trusting

a rumor spread by the police… the comrades ignored the problem of defending

the building. The error is paid for… 300 police intervened in a very swift

action…. They were able to break down the front door despite being bombarded

with bricks and stones… from the windows. The police drove everyone out….

The response of the occupants, especially the proletarian women was immediate….

The will to struggle and win emerged clearly from the mass popular assembly

[called to decide strategy —Ed.]. All those who spoke reached the same conclusion:

struggle until victory, no retreat, mass encampment in front of the building

until all the families were given housing. If the police intervened again

they were ready to put up a violent resistance…. At 11 p.m. the police

made their first charge, which was very violent. They met with an enraged

response: a lot of cops ended up in the hospital, among them a police captain

who was hit over the head with a bottle of milk by a mother. Violent police

charges followed. Tear gas was used.”

The next day, September 26, after seeing the resolve of the twenty

resisting families and the solidarity shown them by the rest of the neighborhood,

the public housing authorities gave in and granted them housing. The violent

struggle had paid off! Sinistra Proletaria distributed a victory statement

which concluded:

“They have won against the revisionists and all the other ‘false

friends of the people’ who preached moderation, who wanted to rely only

on negotiations, who accused the people in struggle of extremism and adventurism.

Revisionists of all varieties said we would be defeated! And instead we

won! The new law of the people has won!”

The changing SP/CPM organization also led a campaign in early 1971

to make transportation free, urging workers to seize buses during rush hours,

and refuse to pay. This struggle did not take on a really mass character

like the housing struggles, since shortly after SP launched the campaign

they went underground. The seeds for a future mass struggle were sown however.

Three years later mass struggles for free transport did explode ail over

Italy.

The one new sector of rebellion that the SP/CPM backed away from was

the feminist movement. At that time the first women’s liberation groups were

forming in Italy. While composed of petty-bourgeois intellectuals, as is

typical of new radical phenomena at first, feminism was a shock to the ingrained

backwardness of Italian society — including the New Left. SP/CPM viewed

women’s oppression as a secondary issue, often as a petty-bourgeois diversion

from

the revolution. Their view was that women needed nothing except to

join their husbands in overthrowing the government. Here is a CPM leaflet

distributed for International Women’s Day in 1970:

Women’s Liberation!?“But liberation in relation to whom? From the husbands who are exploited 8 hours a day in the factory, Liberation so women ‘can work’? Liberation so that women today ‘can’ go to a cafe or movie alone, buy some extra clothing or a necklace, or take the pill? In our society based on exploitation 24 hours out of 24 hours a day: Men have the privilege of being exploited in the factory to ‘main Then in addition in the name of their liberation the bosses offer In this way women are exploited: First, because they have to enter the factory to pay the rent, to Second, because they have to take care of the house, the children — to take away the so-called ‘weight’ of educating your children — ask you to ‘delegate’ to them the authority to educate your To struggle for day care centers means to struggle for our Real liberation comes from the class struggle.”

Metropolitan Political Collective |

The leaflet expresses some good ideas, particularly in the need to

protect children from the State and the so-called educational system. But

the male outlook and narrowness of the leaflet is evident. To belittle women’s

struggle for basic human rights, for the right to a job or the right to go

out in public alone without fear of violence, is chauvinism. Remember that

this was in a society where women were legally not allowed even wage labor

without a husband’s permission.

What was so incongruous about that was the leading role in CPM played

by Margherita (Mara) Cagol. She was an exceptional woman in both senses of

the word. The Italian New Left was still primarily male in outlook and composition.

A revolutionary Left based in certain key factories in heavy herself came

from a middle class family (mother a schoolteacher and father a small cosmetics

store owner) in the far North. She had a very Catholic upbringing, and was

thought to be a serious-minded person by her teachers. It was at Trento,

as a student activist, that she first found the revolution. While her close

comrade and husband, Renato Curcio, became the leading theoretician

of the Brigades, Mara Cagol was a leading militant in her own right. During

the Political Work period at Trento University, she had done social investigation

on peasant conditions in the surrounding Trentino region, and had translated

an abridged version of Karl Marx’s Capital which was widely used in Italian

New Left study circles.

In the Metropolitan Political Collective Mara was among the most

radical. She took a leading role in organizing the new guerrilla formations,

and was to become

the political-military commander of a column of the Red Brigades.

As Renato Curcio wrote of her: “For Mara imperialism was not an abstract

concept but an enemy that you began to fight — in common with comrades —

in your everyday choices.” Mara certainly was exceptional in her commitment

and abilities. But she was also the proverbial exceptional woman whose

abilities even male chauvinists always depend on, and whom they single

out for praise in part as a way to avoid facing the general oppression of

women.

Mara was at the same time a pathfinder for other women who were coming

to join the anti-imperialist armed struggle. As the radicalization of women

in Italy grew, the number of women in the armed struggle rose. However, the

women in the armed struggle and the women raising feminist struggles were

not necessarily the same women. In Italy (as in the “u.s.a.” there was a

profound division among radical women–where armed anti- imperialism and

Women’s Liberation were put in opposition to each other. Neither this nor

the attitude of the BR were static situations, however. The practical effect

this had on the movement will be seen in the national referendum on divorce

in 1974.

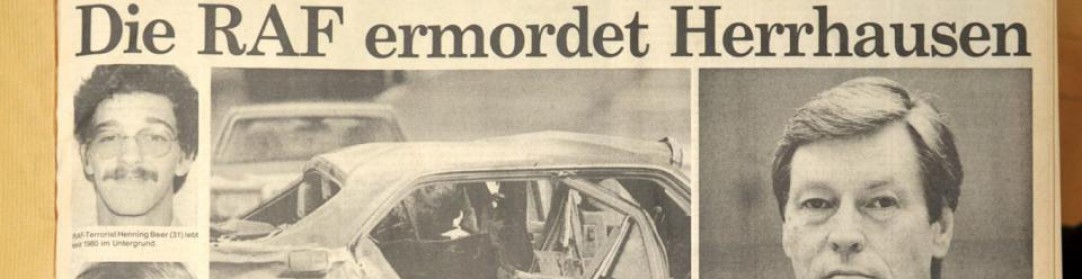

Beneath the public struggles led by “Sinistra Proletaria” in the

summer and fall of 1970, a new organization calling itself the “Red Brigade”

singular at first, and then the “Red Brigades”, began to carry out small

propaganda actions. This was a point where armed activity was also taking

root even in the flinty soil of West Germany, with the appearance of the

Red Army Faction (R.A.F.) In France an armed organization had risen out

of the ashes of the French May 1968 student revolt. The BR felt especially

close to this French group, which began with the same name, Proletarian

Left (“Gauche Proletarienne”) and did the same kind of illegal housing occupations,

bus take-overs and other mass actions that SP used in Italy. European developments

were encouraging. In its September-October 1970 issue SP wrote:

“Guerrilla warfare has now completed its initial phase… it is no

longer simply a detonation… but has taken on the dimension of being the

only strategic perspective that .can historically replace the insurrectionary

one, which is now

inadequate, and… penetrate the metropolis, fusing the world proletariat

in a common strategy and form of struggle. Capital unifies the world through

its project of armed counter-revolution; the proletariat unites itself on

a world scale through guerrilla warfare. ITALY AND EUROPE ARE NOT HISTORICAL

EXCEPTIONS.”